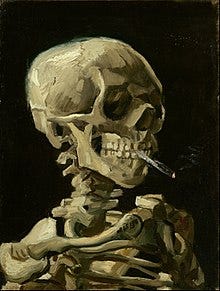

Work & Death

In recent years, I have been trying out a belief, fully expecting someone to contradict it, but no one ever has. Here it is: I believe that every career crisis is a life crisis.

I believe that if you dig into the nutmeat of a career crisis - a time of difficulty or trouble, a time when challenging or important decisions need to be made about work - if you sit earnestly enough with the questions that these times raise, you will eventually encounter more fundamental questions about what it means to be human.

Questions like which major to choose, or what job to take, or whether to press on in a given career path are inklings of their existential counterparts - Why do anything? What does any of this mean anyway?

Ultimately, when we’re grappling with questions about our work, I think we’re grappling with questions about our purpose and the meaning of what we do. That is to say, we are grappling with the fact of death, “the fact that consumes all other facts.”1

Now, jumping into the existential frame is not always the most useful thing to do. Pondering the existential givens can provide useful perspective, but it doesn’t always offer the clearest path forward. However, in many circumstances I’ve found that the ability to cycle between existential, strategic, and pragmatic concerns can help us gain a fuller picture of what’s driving us to pursue certain things - not all of which line up with our desires.

For example, lack of attention to the existential givens can drive one unthinkingly into the grind of workaholism. As Irvin Yalom observed:

“One of the most striking features of a workaholic is the implicit belief that he or she is ‘getting ahead,’ ‘progressing,’ [or] moving up. Time is an enemy not only because it is cousin to finitude but because it threatens one of the supports of the delusion of specialness: the belief that one is eternally advancing. […] Living, thus, becomes equated with ‘becoming’ or ‘doing;’ time not spent ‘becoming’ is not ‘living’ but waiting for life to commence,”2

It’s as if ignoring the reality of death allows us to plunge headfirst into work without considering the tradeoffs that the plunge requires. Said another way, confining the career crisis to the realm of career makes it less cumbersome. Here’s Ernest Becker on the idea:

“Man cuts out for himself a manageable world: he throws himself into action uncritically, unthinkingly. He accepts the cultural programming that turns his nose where he is supposed to look. […] He doesn’t have to have fears when his feet are solidly mired and his life mapped out in a ready-made maze. All he has to do is to plunge ahead in a compulsive style of drivenness in the ‘ways of the world’ that the child learns and in which he lives later as a kind of grim equanimity - the ‘strange power of living in the moment and ignoring and forgetting.’”3

In fact, I think this is why we have career crises at all. We make decisions that are in service of standards we accept unthinkingly or unknowingly that lead us into worlds we didn’t imagine, expect, or want. Then, when we’re stalled, turned around, upended, or otherwise rejected, we’re faced with the unenviable chore of trying to figure out now what?

This is all a very long way of saying, the fact of your mortality is imminently relevant to the work decisions your making. Have you factored that in?

As I said to a friend recently, regardless of what you’re doing, on some level you’re always opting in. You might as well be opting in to do something you find challenging, interesting, enjoyable, or otherwise worth doing.

May, Todd. Death. Routledge, 2014.

Yalom, Irvin. Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books, 1980.

Becker, Ernest. The denial of death. Simon and Schuster, 1997.