What Makes Career Decisions Complex?

On uncertainty, learning by experience, and a place where growth is found.

Today we’re about a quarter of the way through the class that birthed this newsletter. So far in class we’ve talked a little about work itself, making choices, understanding and aligning priorities, and what makes decisions complex.

One thing I’ve realized over the past four weeks is that elements of complex decision making have emerged in the teaching itself. Especially the idea that when you’re making complex decisions, you may not understand all the options or possibilities until you start.

One example from teaching is that I had to make the syllabus weeks before the class started, making big and small decisions about what to teach, how to go about teaching it, and when each topic should appear in the logic of the course. The complexity of syllabus decisions is debatable, but it certainly highlighted the need to just start making decisions in order to better understand what decisions need to get made.

In order to start, you have to get started. This is a paradox with which I’m not entirely comfortable.

Here are just a few more uncomfortable realities of complex decisions:

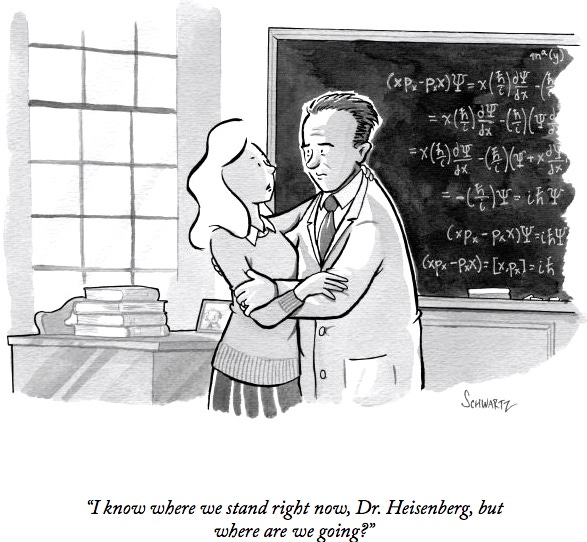

They’re uncertain…

The full suite of options may be unknown

Probabilities of success are unknown or estimated

Success is frequently dependent on how well you execute

Changing circumstances may change your motivations, beliefs, etc.

You may not understand all the possibilities until you start to execute

Your preferences may change in the course of the decision process (e.g., where are my friends going?)

Measures of success may be absent, complex, vague, or may only bear out over a very long period of time

Subsequent decisions may influence the consequences of prior decisions, making it less clear which decisions were successful

You may need to manage stakeholder input, perceptions, goals, etc.

As it turns out, the course structure I settled on has continued to make some sense, so we’ve stuck with it for the time being.

But how I’d planned to go about teaching it - reading and reflection and conversation - has flipped on its head. I’ve continued to learn how experiential the class needs to be, especially at the undergraduate level; that there are elements of complexity in decision making about work that simply don’t make tangible sense until you’ve made more decisions.

Our simulations and cases have brought elements of this to the fore - making choices between a boss’s request and a life priority, for example - but nothing can quite replicate that gut level feeling, the sweaty palms, or the racing mind that can accompany these choices at times.

I’m not sure you can learn - except by experience - that making the right decision for yourself may sometimes simply be uncomfortable.

Another way in which the course is recapitulating its content: Measures of success may be absent, complex, vague, or may only bear out over a very long period of time.

My wife recently asked me how the class was going, and my honest answer is “I have no idea.” The students are sharp and engaged. They do the reading (as best I can tell) and turn in their assignments with thoughtful responses. Does that mean the class is going well?

A quote from James Carse’s book Finite and Infinite Games feels resonant:

Gardening is not outcome-oriented. A successful harvest is not the end of a garden's existence, but only a phase of it. As any gardener knows, the vitality of a garden does not end with a harvest. It simply takes another form.

Gardens do not "die" in the winter but quietly prepare for another season. [...] Inasmuch as gardens do not conclude with a harvest and are not played for a certain outcome, one never arrives anywhere with a garden. A garden is a place where growth is found.

What’s the true measure of success here?

It’s a question as relevant to career decisions themselves as it is to teaching about career decision making.

Nice reflection, Ross. I've found it useful to think of most human processes in terms of being iterative and reflexive. Continuous tiny steps circling their impact on the process.