In the course of doing my work, people sometimes ask me how I got into the field of consulting psychology. This question presents me with a choice, whether to tell the long version or the short version of how I came to do what I do.

The long version includes all the stops and starts, the decision points along the way, the narrowly avoided application to law school, and how I learned over time that I always seemed to be more interested in the people I was working with - what they cared about, how they wound up where they were, what they liked about work - than the work itself, and how that interest now makes up my day-to-day.

The short version includes two critical details: my dad is a consulting psychologist and mom is a psychotherapist.

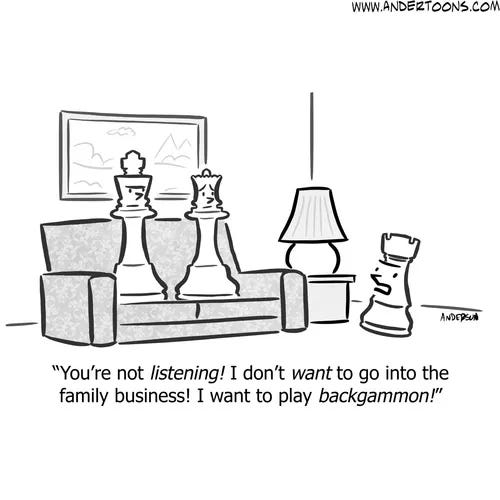

Now, don’t be fooled and assume I willingly went into the family business, as it were.

I diligently ignored my parents’ suggestions that I might enjoy working in the field of psychology, first by simply ignoring them, then by working in the insurance industry, and then in financial services.

Accepting an answer to a complex question from someone else, you see, felt like capitulating. And I wanted to figure it out on my own damnit.

All the while, mind you, I was attending closely to what my friends were doing, trying to emulate (or catch up to) those who seemed to have made all the right decisions.

I recently finished reading the book On Trails by Robert Moor. It’s an interesting compendium of observations and philosophical meanderings about trails and paths in their various literal and metaphysical forms. This passage from the epilogue stuck in my mind, in it Moor writes:

We move through this world on paths laid down long before we are born. From our first breath, there is a vast array of structures already in place - “spiritual paths,” “career paths,” “philosophical paths,” “artistic paths,” “paths to wellness,” “paths to virtue” - which our family, society, and species have provided for us.. In all these cases, the word path is not applied haphazardly. Just like physical paths, these abstract paths both guide and constrain our actions - they lead us along a sequence of steps, progressing toward our desired ends. Without these paths, each of us would be forced to thrash our way through the wilderness of life, scrabbling for survival, repeating the same basic mistakes, and reinventing the same solutions.

As I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’ve gone into the “family biz,” I find myself having these mundane encounters with my parents that I experience as uncanny. I tell them about my work, and they happen to have deep insights into ways of navigating what I’m working on. It’s as if - and I know this may sound absurd - they’ve walked this career path before me.

Later in the epilogue, Moor quotes James Fitzjames Stephen, a judge, writer, and philosopher with an A+ name, who said:

‘We stand on a mountain pass in the midst of whirling snow and blinding mist, through which we get glimpses now and then of paths which may be deceptive. If we stand still we shall be frozen to death. If we take the wrong road we shall be dashed to pieces. We do not certainly know whether there is any right one. What must we do?’

We live in a world that is for many filled to the brim with career choices, at least in theory. Frequently, when I’m working with someone in a career assessment, they’ll tell me at the outset that one of their hopes is they’ll emerge from the process with a Brand New Idea. Some off-the-wall suggestion that they’d never considered before and that is the perfect fit for them.

And yet, one of the first questions I ask in a vocational interview is “what do/did your parents do?”

In so many cases, people are either reacting to or recapitulating what they observed growing up. With a question like this, I’m interested in uncovering a bit of how their theory of work emerged. What’s the inner monologue about work? What’s the familial narrative around how work should be done, and what makes work good? These social influences get baked into our cake pretty early, and we rarely evaluate them, much less question them as we make decisions.

About a month ago, I got a note from a reader who asked, “how should one respond to social pressure [in making career decisions], whether this is from our parents or peers who seem to have it figured out?”

I kept wanting to write about it, but I’m certain I don’t have a good answer. It’s a question I’ve struggled with myself, and one that I’ve been considering since I got the note. I suppose I haven’t written anything about it yet because my response can basically be summarized as “Respond.”

Respond to that feeling of pressure. Interrogate it. Talk it out. Think about where the pressure is coming from, and how it may be informing your perceptions of yourself and decisions that you’re making. These pressures do shape how we understand our circumstances and make decisions, and digging into them a bit at least affords the opportunity to respond to them and make a choice, rather than simply being shaped by them unknowingly.

And one more thing, the illusion that other people seem to have figured it out is precisely that, an illusion. Or, as Anne Lamott said so eloquently, “Never compare your insides to everyone else's outsides.”