When I was in graduate school I had the opportunity to join an executive search firm and start their leadership assessment group. I had just finished my master’s degree and had done a “lunch ‘n learn” with the partners describing how I thought assessments could be incorporated into the executive recruiting process in a useful way.

Part of my presentation was about where I would look to recruit someone who could take on that project for the company. I said something like “find me, but 5 years from now.” But the founder of the firm wasn’t interested in half measures, and asked me if I’d take it on.

At that time I was dead set on finishing my dissertation so I didn’t languish in PhD purgatory (i.e., “ABD” or all-but-dissertation), but I was also really excited by the idea of starting something. I read about executive assessment work. I talked to my parents, and friends, and mentors, and professors, and anyone who I thought could give me some reasonable insight into how good or bad an idea this was (…anxious decider here).

In the course of navigating that decision, one conversation in particular has always stuck with me. A mentor, whom I respect very much, said flat out “this is a bad idea, don’t do it.” His concerns ranged from the practical (“focus on finishing your doctorate!”) to the ethical (“is this something you should be doing this early in your career?”) to the career-existential (“you could get sued and ruin your career in this field before you even get started.”).

His reaction was so quick and so certain that it made my stomach hurt. It set off a vicious spiral of self-doubt: Was I deluding myself into thinking this could be a good opportunity? Would he look at me differently if I took the job? What was I thinking? How would I possibly make this work?

Here’s the thing, I took the job.

A few weeks later that same mentor called me to apologize.

I don’t remember much from that conversation, but I remember my surprise that he’d reversed course. That perhaps his own fears had gotten in the way of advising me, and that he thought I’d actually made the right decision for myself. I also remember that he encouraged me to continue making decisions like that, as he put it:

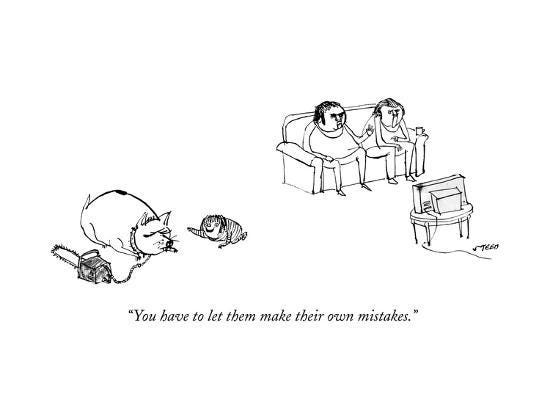

Make no small mistakes.

Or, as I heard it: you’re going to make mistakes, and if you only make small mistakes, you’re not risking enough; if you only ever do what’s comfortable, you’re not growing, you’re not learning.

This week I turned 37. As a friend counseled, still ‘mid-to-late-thirties.’

Birthdays have lost some of their sheen as I’ve gotten older. It’s not that I don’t enjoy them per se, but I find that the dominant emotion I tend to have on my birthdays - if it can be called an emotion - is dislocation. A disturbance from my usual state. I become more reflective and sort of float around wondering where time has gone and how I’ve wound up where I’ve wound up. It’s not exactly unpleasant, but it is largely unproductive.

Except, I think this kind of dislocation can serve a purpose. I don’t bemoan aging, and it’s not a mortal fear that pops up, but something more like anticipated regret. Questions like “am I doing The Right Thing?” Or “am I playing it too safe?”

I’m not so sure there’s a way to answer those questions, though I’ve found one thought experiment useful. I zoom off into the future and try to imagine myself looking back on some decision to consider will I regret not having tried?

There’s a cliche or two baked that you’ve probably heard: “What would you do if you knew you couldn’t fail?” Or more to the point: “What would you do if you weren’t afraid?” I dislike these cliches because the possibility of failure and fear are constant companions, especially when you endeavor.

I think the better question to ask, as I imagine myself off in the future looking back is, “What were you so afraid of?”

Recently, in his newsletter Story Club, the esteemed writer George Saunders wrote about cleaning out his old office. In doing so, he discovered a binder full of stories with a letter pinned on the front that he’d written to himself after completing and then shelving the whole project. It’s entitled “Notes on Progress, May 24, 1989” and reads like a writerly diary entry about what’s going wrong in his writing and how he intends to rectify it:

I have nothing to offer the world when I am careful. There are smarter, more articulate, more organized, and more artistic people than myself. But I have my sense of beauty. My work must be the expression of that, in whatever form is needed. Fuck artifice and the imaginary voices of short-story purists, etc. Listen only to your memory. What comes will be beautiful.

I love the line, “I have nothing to offer the world when I am careful.” As though the more he tries to put on a front, the more he tries to fit into some kind of imagined mold, the less of himself he is accessing and offering the world.

I wonder if this could be turned into a sort of Mad Libs exercise. A way of checking in to the imaginary voices that may be saying “don’t” or “you can’t,” and how you might counter those thoughts. How would you fill in the blanks?

I have nothing to offer the world when I am careful.

There are ____________________, more ____________________, more ____________________, and more ____________________ people than myself.

But I have my ____________________.

My work must be the expression of that, in whatever form is needed. Fuck artifice and the imaginary voices of ____________________, etc.

Listen only to ____________________.

What comes will be beautiful.