At the end of every episode of the podcast How I Built This, Guy Raz asks his (incredibly successful) guests, “Do you attribute your success to luck, or hard work and skill?”

It’s usually a predictable response, but I always enjoy this question. It’s like an ongoing study in attribution theory - how people perceive the causes and effects of their (and others’) behavior.

My favorite response to this question; however, occurred on The Ezra Klein Show. Klein asked the author Michael Lewis why he was so good at his work, and Lewis said that he loves what he does and doesn’t really view it as work. “That,” he said, “and huge amounts of luck.”

To this, Klein said, “So, a rule I have is that people who attribute everything to how good they are, are usually really lucky; and people who attribute everything to how lucky they are, are usually pretty damn good.”

What a perfect definition of imposter syndrome: people who are pretty damn good at what they do but attribute their success to luck. The more academic version is “high-achieving individuals who, despite their objective successes, fail to internalize their accomplishments and have persistent self-doubt and fear of being exposed as a fraud or imposter” (Bravata, Watts & Keefer, 2020).

Studies suggest that imposter syndrome can be a self-fulfilling prophecy - consistent doubts about professional legitimacy are correlated with lower self-esteem, fear of failure, and decreased motivation (Bravata, Watts & Keefer, 2020).

I speak with someone every week who says they feel like an imposter at work. I suppose this shouldn’t surprise me because it’s estimated that 3 out of every 4 people will feel like an imposter at some point in their professional lives (Bravata, Watts & Keefer, 2020; Chrousos, Mentis & Dardiotis, 2020).

It has become such a common occurrence that I now believe feeling like an imposter in your work says less about you, and more about our organizations and our culture in general.

Perhaps it’s a slow-burning side effect of social media posturing and online credential flexing; or maybe it’s more indicative of how we have come to view expertise and high performance?

As Oliver Burkeman put it, “Imposter syndrome [is] worse than you think – because you think the issue is that you don't yet have the qualifications to hold your own among your colleagues, when in fact the truth is that everyone is winging it, all the time, and that if you're ever going to make your unique contribution to the world, you're going to have to do it in a state of unreadiness.”

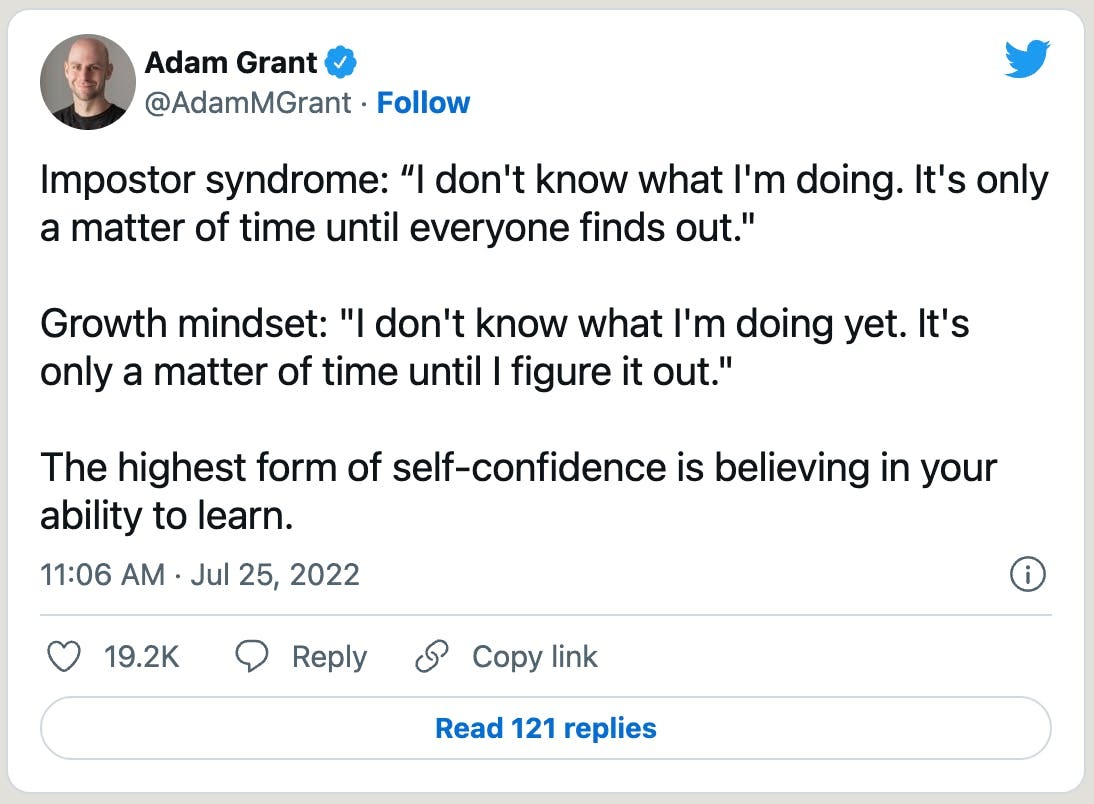

Which is to say, feeling like an imposter is most likely simply a signal that you’re learning.

Or that you’re adapting to a new environment. Or that you're inquisitive and you’re questioning your methods. Or that you can evaluate how you’re doing and know when you might need guidance or help.

This cognitive bias is so predictable that it has a name, the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

Dunning-Kruger shows how people with less knowledge and expertise tend to overestimate their ability and people with more knowledge and expertise tend to underestimate their ability. It’s an effect that you might describe as “the more you know the more you know you don’t know.”

The common recommendation for feelings of imposter syndrome essentially amounts to “now that you know that, don’t feel that way,” which has the same efficacy as me telling you not to think of a pink elephant.

The best treatments for imposter syndrome are coaching/mentoring that involves talking about those feelings directly, therapy if it’s comorbid with other symptoms like depression and anxiety, and the best solution - group coaching/counseling where everyone can see that everyone else has/does experience the same feelings. All of which suggest that most of the negative effects of imposter syndrome thrive on the feeling that you're the only one and that no one else feels this way. In fact, most people do, or at least have at some point. It's part of the process.

It’s also worth remembering that people who don’t experience imposter syndrome are either a) entirely un-self-aware (or lying), or b) deeply experienced people who no longer think about the conditions of their success or the outcomes of their effort, they just focus on doing the work.

***

Bravata, D. M., Watts, S. A., Keefer, A. L., Madhusudhan, D. K., Taylor, K. T., Clark, D. M., Nelson, R. S., Cokley, K. O., & Hagg, H. K. (2020). Prevalence, Predictors, and Treatment of Impostor Syndrome: a Systematic Review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(4), 1252–1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05364-1

Chrousos, G. P., Mentis, A. F. A., & Dardiotis, E. (2020). Focusing on the Neuro-Psycho-Biological and Evolutionary Underpinnings of the Imposter Syndrome. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(July), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01553