A Mathematical Argument for Quitting Your Job

On optimal stopping, boredom, and utopian goals.

Bear with me. There’s this math theory called optimal stopping that involves using probability to decide when to take a certain action in order to maximize gains (or minimize losses).

This Washington Post article lays it out pretty clearly as it relates to dating.

Essentially the theory suggests that in order to make the best choice you should reject the first 37% of options you get, then go with the next option that’s better than any of those that came before it.

Let’s say, on average, you hold 12.4 jobs over the course of your career. But half of those jobs you have before age 25, so for the sake of ease, let’s say you’ll have 6 jobs in your adult life.

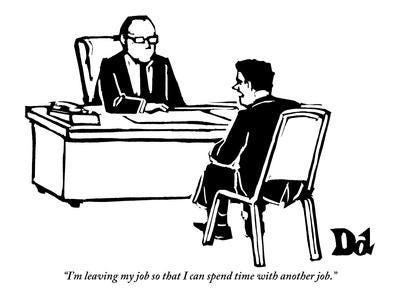

If we take the theory of optimal stopping quite literally, that means you need to quit the first 2.22 jobs that you have, then “choose” the the next job you get that’s better than all those that came before it.

Easy enough.

This little thought experiment raises a few questions I find interesting:

How many jobs have you quit? Whether it’s moving away from something or moving toward something, what does your “dataset” of different kinds of work experiences and environments consist of?

What kind of feedback are you using to make career decisions? Are you more focused on an abstract model of what you think “good work” should look or feel like? Or are you using the information you have about what has made work more or less engaging for you in the past? That is, do you compare what you’re looking for in a job to what you’ve experienced or what you desire?

Is it necessary to quit to solve this problem? To paraphrase some advice I’ve heard my dad give, sometimes the mistake people make is not giving a job enough time or digging into their work deeply enough to find what’s interesting about it. Or, as the composer John Cage put it, “If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all.”

By my count, I’ve quit four jobs in my adult life.

Each time it felt like a necessary step toward something better. One thing I like about the quit two jobs then pick the next best one idea is that it implies a sort of triangulation. If you’re paying attention to the feedback you’re getting on the job - tuning in to what’s energizing you, what’s wearing you down, and where you’re getting positive feedback - you could have a pretty good sense of what you’re aiming for by your third at bat.

I also think this idea puts a lot less pressure on those early decisions. Expect that you won’t land in the right spot in those first few jobs, but that you’ll be gathering important information about yourself, what you like to do, what kinds of environments you enjoy working in, etc. The goal is simply to learn, observe, and experience.

And if you’re bored, what might you do to dig in a bit further, to gather a bit more information about your present circumstance. At worst, you’ll have more data to take with you when you go, at best, you may find something grabs your attention.

An important problem with this thought experiment is that new job opportunities don’t tend to appear randomly, so decision methods based only on probability (like this one) can’t be applied with the same expectation of success as games of pure chance.

But there is a useful, if partially obvious, point here:

You have to quit your job to find a better job, and you have to be open to the idea that quitting your job may not necessarily lead to a better solution. To paraphrase the psychologist Paul Watzlawick, utopian goals can become their own kind of problem.

A potentially relevant observation: writing about quitting is uncomfortable. I’m a bit uncomfortable writing this right now, and all I’m doing is sitting at my comfortable desk typing.

The designer Liz Danzico makes an useful point about this:

Our culture scorns switching and quitting. We don’t celebrate stopping things, changing our paths, or our minds. Just the opposite. We celebrate finishing things.

We’re so busy tracking completion — how many miles run, books read, calories burned, cities visited — that we forget to remember a project’s value in the first place.

We get so caught up in avoiding the social discomfort associated with this kind of change that we resign ourselves to our current circumstances, even when it is painfully obvious that something needs to change.

Is there something you would quit doing today if you knew it would lead to something better? Let me know in the comments below.

Apply this Thinking

Quitting and the associated discomfort of it falls into the category of things that are useful to talk to someone about. Walk through your thinking with someone else. If you’re thinking about quitting your job, lay out the case for it and the case against. What’s the pragmatic decision? What’s the strategic decision? What’s the decision that will best align you to your core values?

If you’re stuck, Annie Duke recommends making “Quit Criteria.” Write down metrics and dates that can serve as gating items for you to continue on. For a creative project this may mean working on something until a certain date and quitting if XY or Z milestone still hasn’t been reached. For a job it may be a promotion, or a move, or a revenue number. The more specific, and the more committed you can get to acting on the standards you set, the better.

Try this method only when you’re single and in your twenties...quitting later in one’s career is much more complicated process. I did it. It worked. It took years of planning due to mortgage, kids, etc.